Condition to Play Every Shift Like Your First: Part 1

The days of walking into the gym and only lifting weights are long behind you. High level hockey performance programs now including mobility, hip and core strength, dynamic warmups, change of direction, acceleration, max speed, power, and total body strength. But the one area that’s lacking in many up-and-coming hockey players is their preparation with their conditioning.

Some players just simply don’t like to condition or don’t think it matters. When you’re young, being big, strong, or fast can allow you to have success against smaller, weaker, and slower opponents late in games. Eventually, other players will mature and continue to train, catching up to the poorly conditioned athletes and exposing their weaknesses.

Other players have the mindset that all their conditioning should be done on the ice, leaving the gym right when they’re done lifting. While that’s well intentioned to be “sports specific,” this will put additional unwanted stress on the adductors and hip flexors, may limit the central (heart) adaptations because of peripheral (leg) fatigue, and is almost impossible to do low intensity aerobic work.

And other players have the mindset that they should run cross country or play soccer in the off-season to work on their conditioning. This has its own downfalls as both are their own specific sports and may get you in better aerobic shape, but don’t account for the high intensity side of hockey, as well as the lower body muscular endurance required.

Running cross country to get in better shape would be like joining a powerlifting team to get stronger. There are plenty of solid training concepts that players can take from the realm of powerlifting and add to their strength program. And there’s plenty of cross-country principles that can be added to their conditioning program. But, by going through another sport, you will perform plenty of training that will have no transfer to the sport of hockey.

If this was the best option, the sport of hockey would be full of cross-country runners and powerlifters.

P.S. I’m not saying that young athletes shouldn’t play other sports. There’s a ton of research on playing other sports for long-term athletic development and that’s an article for another day. This point is only about playing another sport for the sake of getting in better shape for hockey.

The reality is that hockey conditioning falls somewhere in the gray area between all three of the above examples. You need to condition, but not condition too much that it blunts other aspects of your development. You need to do aerobic work, but not so much that you don’t do any anaerobic work. And you need to be on the ice, but not so much that you’re putting yourself at a higher risk of injury.

21st Century Hockey Conditioning

For years, hockey players have been coached to perform 45-seconds of all out work with two to three minutes of rest because it’s “specific” to a hockey shift. The issue is that a shift is never 45-seconds of all out work; it’s comprised of multiple very short, very high intensity sprints that are broken up by slow skating, gliding, and standing. Players average about seven high intensity sprints per shift, with 56% of total skating distance performed at very slow, slow, and moderate skating speeds. Knowing that, hockey conditioning should focus on the alactic system (<10-seconds in length) to provide energy for high intensity efforts and the aerobic system (>5-minutes in length) to improve recovery between sprints, shifts, periods, and games.

Let me introduce you to “working the V.”

Working the V is a concept that I first heard from coaches that I look up to, Anthony Donskov and Mike Robertson. This is when most of the off-season will focus on the alactic system and the aerobic system, with the end phase(s) of the off-season focusing on the lactic system to get prepared for the upcoming tryout or training camp. The longer the off-season, the wider the V becomes. The shorter the off-season, the narrower the V becomes.

Being able to tolerate high levels of acidosis in the body, while still performing with high levels of force production and mental clarity, makes the lactic system still utterly important. The 45-second all out work coaches make players do has merit, just not for the reasons they think. Hockey practices are lactic in nature, so ending the off-season with lactic conditioning is important to prepare the body for the stress to come at the start the year.

The main issues with the lactic system are that it is very fatiguing work and the ceiling for improvement is low, with improvements that typically plateau at 6-weeks of training it. To combat that, the off-season should finish with 1-2 phases of 3-6 weeks total of training the lactic system so you can get all the benefits, without spinning your wheels for longer than 6-weeks for no additional improvements. And following those 1-2 phases, you should deload for 5-7 days prior to your tryout or training camp so that all the fatigue that built up over the last 3-6 weeks can dissipate, allowing you to be at your best when the season gets going.

The once popular aerobic training took a back seat for many years due to a high intensity interval training (HIIT) push. While there are plenty of athletes and coaches that are coming back to aerobic training, there are more options in the arsenal than just running endless miles.

Cardiac Output – Cardiac output is what’s commonly thought of when the public thinks of aerobic conditioning. This is also known as steady state, or more recently popularized as zone-2 conditioning.

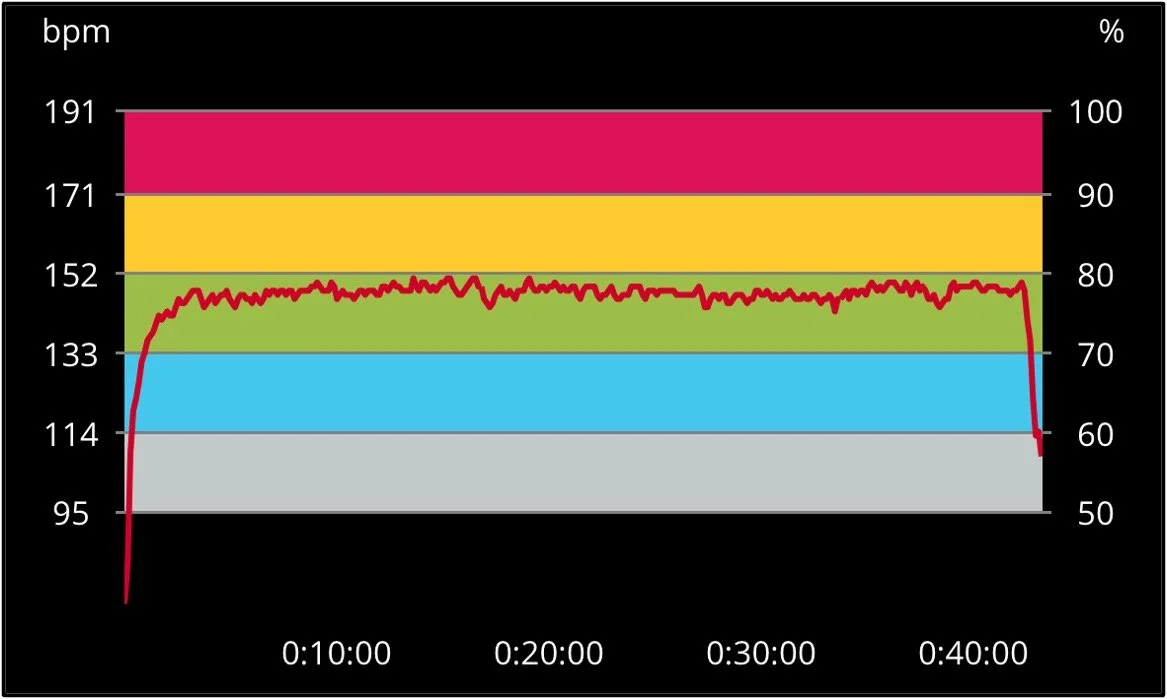

One of the key pieces to aerobic training is the ability for your heart and cardiovascular system to supply oxygenated blood to the muscles. By staying within a specific heart rate intensity, you can increase the size of the left ventricle of your heart, which increases the amount of blood that can be pumped out with each beat to the muscle. Think of a balloon being constantly filled with water and over time it stretches to become bigger, only the balloon is your heart, and the water is your blood moving through it.

The intensity is extremely important because if your heart rate is too high, there’s not enough time for the heart to fully fill with blood. And if your heart rate is too low, there’s too much time between beats to create the “stretching” effect of the heart. The sweet spot is between 120-150 bpm. If you’re younger, you can go on the higher end, and if you’re older, you can go on the lower end.

Cardiac Power – This is the other side of the coin to improving the ability for your heart and cardiovascular system to supply oxygenated blood to the muscles. This method is designed to increase the strength of your cardiac muscle fibers with high intensity work.

By completing 1- to 2-minute bouts where your heart rate gets as close to maximal as possible (>90%), you can increase the strength of the cardiac fibers (because your heart is a muscle too!). This creates a more forceful contraction with every beat, which will cause an increase in how much blood it’s pumping to the working musculature.

Oxidative Tempos – While most aerobic training is thought of as what the heart and cardiovascular system is doing to send oxygenated blood to the muscles, how the muscle fibers utilize that increase in oxygenated blood needs to be thought of too.

Oxidative tempos are exercises that focus on improving the aerobic abilities of the slow twitch muscle fibers. Because these fibers are already highly aerobic, increasing their cross-sectional area (size) is the most effective way to improve their aerobic abilities.

By performing sets of compound exercises with a 2-second eccentric and 2-second concentric, with no pauses at the top or bottom of the movement, you will specifically target the slow twitch fibers. Perform 8-10 reps utilizing a 1:1 work: rest ratio at 25-35% of 1RM and you’ll feel slow twitch hypertrophy gains that you didn’t even know existed.

High Intensity Continuous Training – The other side of that coin is improving the aerobic abilities of your fast twitch muscle fibers, which are not inherently aerobic like the slow twitch fibers.

By utilizing a very high resistance, you can use your fast twitch muscle fibers with a slow speed that will not be fatiguing like other high intensity methods. This is both high intensity and high volume.

Perform this method with a push-pause tempo (20-30 reps per minute) for a total time of 20-40 minutes. This can be broken up into multiple shorter blocks utilizing high resistance bike, high resistance versaclimber, high box step ups, weighted lunge walks, sled drags/pushes, etc.

If you made it this far, thank you so much for reading! My goal with all of these posts is to educate, and one of main components of that is keeping the reader’s attention. That’s why I’ve broken this post in to two parts. Part 2 will be posted next week, and will be going over anaerobic training concepts, as well as how to pull it all together over an entire off-season (or in-season!). In the meantime if you have any feedback on if you think the length of this post or others are too short, too long, or just right, please share that!