Condition to Play Every Shift Like Your First: Part 2

Aerobic training is massively underrated for hockey performance. Last week, I wrote about it here, and if you haven’t read that, I would start there before moving forward. To be clear, as an aerobic training advocate, people might assume I’m telling my athletes to only perform aerobic conditioning and that couldn’t be further from the truth. The end goal is elite repeat sprint performance. That means you should be as fast in your last shift as your first shift, but not at the expense of that “fast” skating in your first shift being below average.

A big mistake coaches make when using anaerobic conditioning, is either extending the work durations too long, making the session lactic when the goal was alactic development, or they shorten the rest periods too drastically, which doesn’t allow for high speeds and forces to be displayed during the work bouts due to fatigue.

Let’s go over my favorite anaerobic training protocols.

High Resistance Intervals – Unlike most alactic training, high resistance intervals uses low speeds, but high resistance (load) to activate the fast twitch muscle fibers. By activating the fast twitch muscle fibers for short durations (<10-seconds), they will be fatigued but not fully depleted. Then, utilizing incomplete rest, you will continue to complete reps to train the endurance of your fast twitch muscle fibers.

Common modalities that could be used are sled pushes, sled sprints, hill sprints, heavy bike sprints, etc.

Alactic Capacity Intervals – Alactic capacity intervals are traditional in the sense that they activate fast twitch muscle fibers with speed rather than load. By keeping the bouts of work at high speeds for short durations (<10-seconds), the muscle fibers will be fatigued but not fully depleted. Just like before, by utilizing incomplete rest, the endurance of these fast twitch muscle fibers will be trained.

For this method, you will utilize short shuttle runs (50- or 75-yards), different jump or KB swing variations, assault bike sprints, or light resistance spin bike sprints.

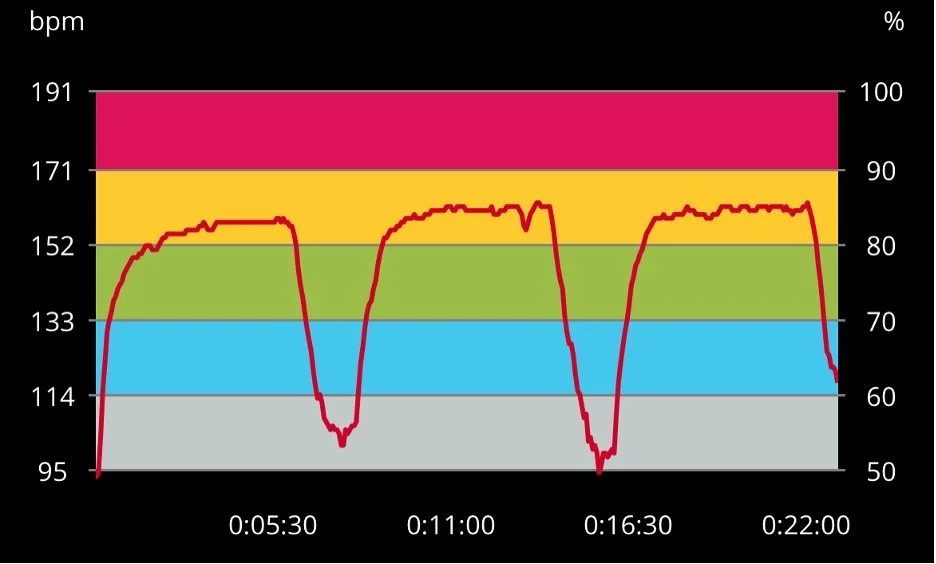

Threshold Training – Your body is always producing lactic acid; you just don’t typically notice because the body can clear it faster than it’s being produced. The intensity where your body begins to produce lactic acid faster than it can be cleared is known as the anaerobic, or lactic, threshold. For most individuals, their anaerobic threshold is ~85% of their max heart rate.

Exercising above your anaerobic threshold can be extremely fatiguing and cannot be sustained for long periods of time. With threshold training, you will perform extended bouts of work +/- 5 bpm within your anaerobic threshold, which will push your anaerobic threshold to a higher percentage of your max heart rate. By doing this, you will be able to sustain higher power outputs while continuing to use aerobic processes, which will cause you to be less fatigued (i.e. feeling fresher) when you’re on the ice.

Circuit Training – I believe circuit training has become popular because some athletes don’t like to perform conditioning, and the fact that you can lift weights as conditioning appeals to them. While they might think this is good aerobic training, circuits are actually great for lactic training. By performing compound movements as explosively as possible with minimal rest, high levels of lactic acid are built up.

Because circuit training will occur in lactic phases at the end of the off-season, this allows you to use more “sports specific” movements as your compound exercises. Choose movements like 1-leg squats, lateral lunges, and cable rotational patterns to train the deep hip, knee, and ankle range of motion that will occur on the ice, as well as the planes of movement that the body must move through.

Lactic Intervals – The body has lots of mechanisms in place to buffer lactic acid, but for those mechanisms to improve, the body needs to be exposed to high levels of fatigue. Performing all-out bouts of work from 20-90 seconds, with 1-3 minutes of rest creates this very acidic environment in the body where it must find ways to bring the body back to homeostasis.

Pulling it all together

In a full off-season plan, you can think of an off-season as six phases. Sometimes this can be longer or shorter, but as a general starting point, use six phases. Within a week of each phase, a high-low model should be followed where Monday, Wednesday, and Friday are the “high” days, Tuesday and Thursday are the “low” days, and the weekend is off completely.

You should start the first phase of the off-season with an aerobic phase, so you can have higher levels of recovery between the high intensity bouts of work to come in later phases of the off-season.

The lifting on the high days will use the oxidative tempo method or high intensity continuous training. The conditioning that will be paired on that day will be cardiac power. The low days will just be focused on long duration mobility, as well as hip and core strength. To make sure the low days stay low, cardiac output method should be utilized on this day.

Phases two and three will be strength phases, so the lifting on the high days will be focused on improving force producing capabilities. To make sure the conditioning pairs appropriately with that lifting, the main conditioning method used will be high resistance intervals. The theme on the low days remains the same, but tempo runs should be introduced. These can be viewed as interval-based cardiac output rather than steady state cardiac output. My favorite work to rest ratio is 15 seconds on, 45 seconds off, eventually progressing to 20 seconds on, 40 seconds off (all done at a 75% effort).

Phases four and five are the speed phases, so the lifting on the high days will be aimed at improving the speed of contraction. Like in the previous phases, you want the conditioning to pair appropriately so you should perform alactic capacity intervals on the high days during these phases. On the low days, you will still perform tempo runs, likely progressed to 20 seconds on and 40 seconds off by this point.

The last phase of the off-season is a lactic phase so you can get as prepared as possible for the upcoming tryout or training camp. For that, you will perform most of your lifting within circuit training to build up high levels of lactic acid in the blood. Following the lifting, you should perform lactic intervals, which doubles down on the effectiveness because there is already fatigue built up heading into the conditioning (squat and split squat holds can also be used prior to conditioning for this same purpose). Because this style of training is so fatiguing, the low days should be lower than in previous phases (this is also considering that you will be skating the most during these weeks and will have fatigue built up from that). To balance that, the low days should include cardiac output method or can be off completely.

When looking at the in-season, this is when conditioning should be completely individualized. For most, practices and games should cover all your needs for conditioning. But, if you aren’t practicing as frequently, or you’re a low minute player, then you should supplement with extra conditioning off the ice (always after practices so you’re not fatigued going on to the ice).

If you’re a player that struggles to keep up with the pace of play due to your speed, you should supplement with alactic capacity intervals. If you’re a smaller player that tends to lose net front battles and can get pushed around, you should supplement with high resistance intervals. And if you’re a player who is fast and strong but have difficulty recovering between your high intensity bouts of work, then you should supplement with cardiac output and cardiac power training.

Everyone has a genetic ceiling for physical qualities like strength, speed, and power, but I don’t think many are even scratching the surface for what their conditioning could be. Unfortunately, conditioning is hard, so it scares off many players from wanting to develop that quality to a high level. Proving to yourself, and your coaches, that you’re willing to put in the effort to be the best conditioned player on the ice is just icing on top of the cake. Remember, it doesn’t matter how fast you are in your first shift, it matters how fast you are in your last.